Practical Introduction to Curvature

Abstract

An intuitive pedagogical approach to understanding curvature in differential geometry. Starting from embedded 2 dimensional surfaces, we explore the concept of curvature before. After feeling the need to treat such objects independently of the way the lie into the 3 dimensional space, we introduce the key concepts of differential geometry and reformulate our prior work in this new frame.

A practical introduction to curvature

Introduction

I remember being very frustrated the first time I studied Riemannian geometry for the following reason : everyone has an intuitive idea of what "curvature" means yet the differential geometric tools that are firstly introduced (covariant derivative, Riemannian tensor...) are quite complicated and seem, at first, unrelated to our naive conception of curvature. It’s only in the end, after being familiar with this complex machinery that one can apply it to study embedded 2 dimensional surfaces and relate it to our prior conception of curvature.

This paper is an humble attempt, for pedagogical purposes, to go the opposite way : start from our familiar conception of curvature to motivate the introduction of the aforementioned mathematical objects. Some proofs are missing and some are not fully rigorous, most of the time, they aim at infusing the reader with geometric intuition.

We will use the term "smooth" for a map that is \(C^{\infty}\).

Curvature of embedded surfaces

In the following section we write \(\langle .,. \rangle\) for the standard scalar product on \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\) and \(\lVert.\rVert\) the associated norm.

We recall that for any smooth map \(\gamma : [a,b]\to\mathbb{R}^{n}\) with \([a,b]\subset\mathbb{R}\) an interval, the length of the curve \(\gamma\) is \[\int_{a}^{b}\lVert\gamma'(t)\rVert dt\].

Curvature in one dimension

One should think of curvature as the opposite of being flat or straight. What characterizes flatness? A flat curve (i.e. a line) should have a "constant direction" : one should always go in the same direction as one moves along the curve.

We clarify what the words "curve" and "moving along" it mean to us in the following definition.

Definition 1. A curve \(\mathcal{C}\subset\mathbb{R}^{2}\) is the image of a map \(\gamma : I=[a,b] \to\mathbb{R}^{2}\) with \(I\subset\mathbb{R}\) an interval such that

\(\gamma\) is smooth.

\(\gamma\) is injective.

\(\gamma\) is a homeomorphism onto its image.

\(\gamma'(t)\neq 0\quad\forall t\in I\).

We say that \(\gamma\) is a parameterization of \(\mathcal{C}\).

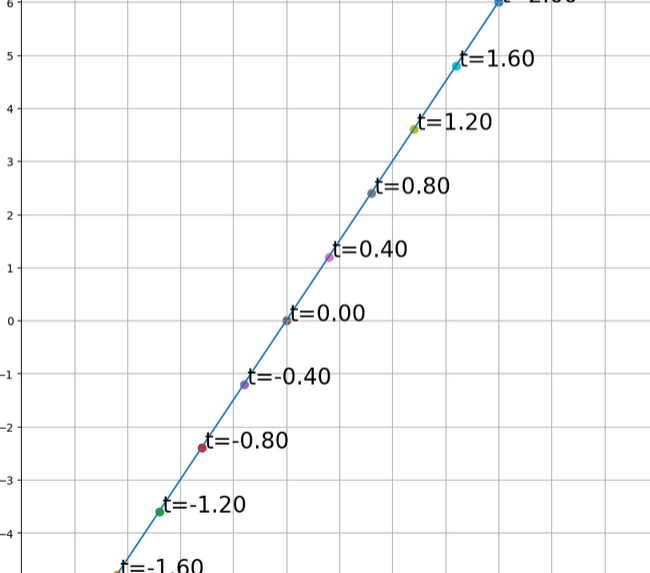

On the left figure \(\gamma_{1} : t\in\mathbb{R}\to (2t,3t)\in\mathbb{R}^{2}\)

On the right figure \(\gamma_{2} : t\in[0,\pi]\to(\cos(t)\sin(t))\)

The requirement (iii) is not redundant for a map that satisfies (i) and (ii). A classical degenerate case is the map \(t\in]-\pi,\pi[\to (\sin(t),\sin(2t))\in\mathbb{R}^{2}\).

We will indistinguishably use the term curve for either a parameterization or its image when there is no ambiguity.

Granted a parameterization \(\gamma\) we can now differentiate this map to get a vector field along the curve. A flatness criterion should be that the derivative of \(\gamma\) is constant i.e. that its second derivative vanishes.

On the left figure \(\gamma_{1}'(t)=(2,3)\). On the right figure \(\gamma_{2}'(t)=(-\sin(t)\cos(t))\).

There is a problem with our approach : a curve may admit several parameterizations and choosing one among the others yield different derivatives. For the straight line above, if we choose \(\widetilde{\gamma_{1}} : t\in\mathbb{R}\to(2t^{3},3t^{3})\in\mathbb{R}^{2}\) then the derivative is not constant anymore even though \(\widetilde{\gamma_{1}}\) parametrizes the same curve.

Nevertheless, we observe that \(\widetilde{\gamma}'\) is always pointing in the same direction.

A different vector field from a different parametrization of the line.

\(\gamma_{1}\) and \(\gamma_{2}\) were good parameterizations in the sense that they had constant speed : \(\lVert\gamma_{1}'(t)\lVert\) (resp. \(\lVert\gamma_{2}'(t)\lVert\)) is constant equals to \(\sqrt{13}\) (resp. \(1\)) which means that one moves along the curve at the same velocity.

If it’s not the case can we construct a diffeomorphism \(\phi : [c,d]\to [a,b]\) such that \(\widetilde{\gamma}=\gamma\circ\phi\) verifies \(\lVert\widetilde{\gamma}'\lVert=1\)?

Such a \(\phi\) should verify \(1=\lVert\widetilde{\gamma}'(t)\lVert=|\phi'(t)|\times\lVert\gamma'(\phi(t))\lVert\quad\forall t\in [c,d]\iff |\phi'(t)|=\dfrac{1}{\lVert\gamma'(\phi(t))\lVert}\quad\forall t\in [c,d]\).

If we define \(\psi : [a,b]\to \mathbb{R}\) by \(\psi(t)=\int_{a}^{t}\lVert\gamma'(s)\rVert ds\) then \(\psi'(t)=\lVert\gamma'(t)\rVert>0\) so \(\psi\) is strictly increasing. It is a diffeomorphism from \([a,c]\) onto its image \([0,L]\) with \(L=\int_{a}^{b}\lVert\gamma'(s)\rVert ds\) the length of \(\gamma\).

If we set \(\phi=\psi^{-1}\) we obtain the desired parametrization called parametrization by arclength.

Definition/Proposition 1. A curve \(\gamma : I\to\mathbb{R}^{2}\) is said to be parametrized by arclength or an unit-speed curve if \(\lVert\gamma'(t)\lVert=1 \quad \forall t\in I\).

Every curve admits a reparameterization by arc length.

If \(\gamma\) is parametrized by arclength then \(\gamma''(t)\perp\gamma('t)\quad \forall t\in I\).

Proof. (i) is already proved.

(ii) Let \(f:I\to\mathbb{R}\) defined by \(f(t)=\lVert\gamma'(t)\lVert^{2}\) then \(f\) is constant and \(0=f'(t)=2\langle\gamma'(t),\gamma''(t)\rangle\). ◻

Observe that, thanks to (iii), arclength parameterization forces \(\gamma''(t)\) to live in the orthogonal of \(\gamma'(t)\) and \(\lVert\gamma''(t)\lVert\) will measure how curved is \(\gamma\) near \(\gamma(t)\) as we shall see.

Let’s now look at the simplest curves that are not flat : circles. Let \(\mathcal{C}_{R}\) denote the circle of radius \(R\) centered at the origin.

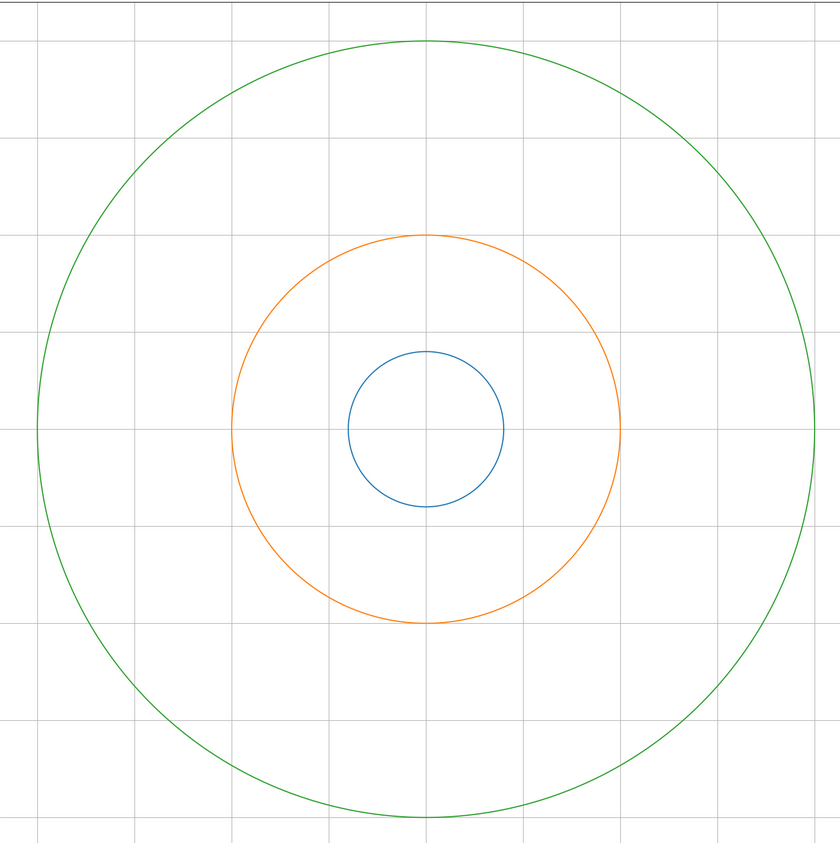

Circles of different radii.

Even if circles are not curves as defined in definition Definition 1 they’re still images of smooth maps from \(\mathbb{R}\) to \(\mathbb{R}^{2}\) that admit an arclength parameterization \(\gamma_{R}:[0,2\pi R]\to\mathbb{R}^{2}\) defined by \(\gamma_{R}(t)=(R\cos(\dfrac{t}{R}),R\sin(\dfrac{t}{R}))\).

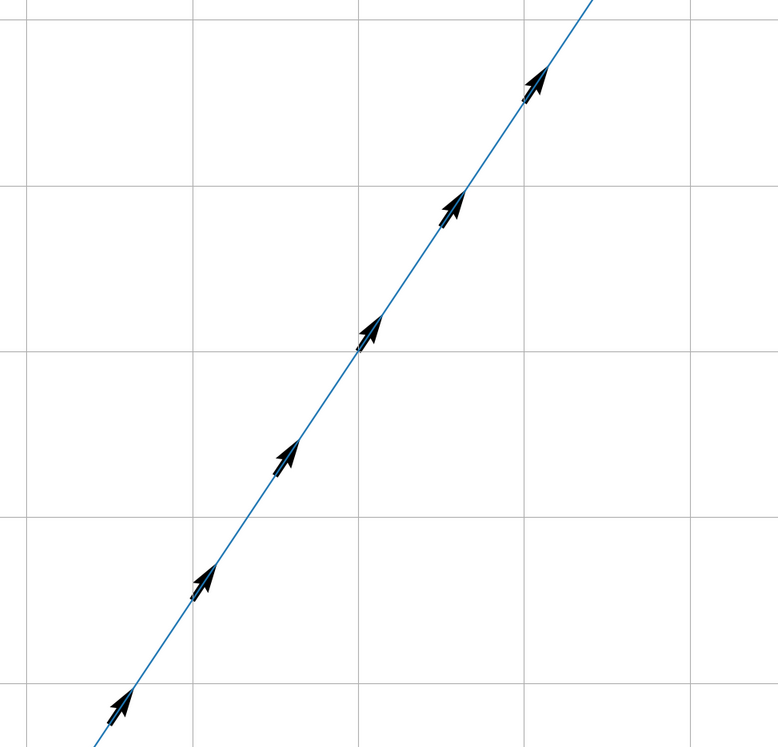

The vectors represent \(\gamma_{R}'\) and have constant length. The greater R is the less their direction fluctuates.

At the beginning of the section, we observed that a line is flat because the second derivative of its arclength parameterization vanishes so we could expect that \(\lVert\gamma_{R}''\lVert\) is a good candidate to quantify the obstruction to being flat.

We can compute \(\lVert\gamma_{R}''(t)\lVert=\lVert(-\dfrac{1}{R}\cos(\dfrac{t}{R}),-\dfrac{1}{R}\sin(\dfrac{t}{R}))\lVert=\dfrac{1}{R}\). We observe that the larger \(R\) is the less curved is the circle and it makes sense : earth appears flat to us because of its very large radius.

The vectors represent \(\gamma_{R}''\) and their length decreases as R increases.

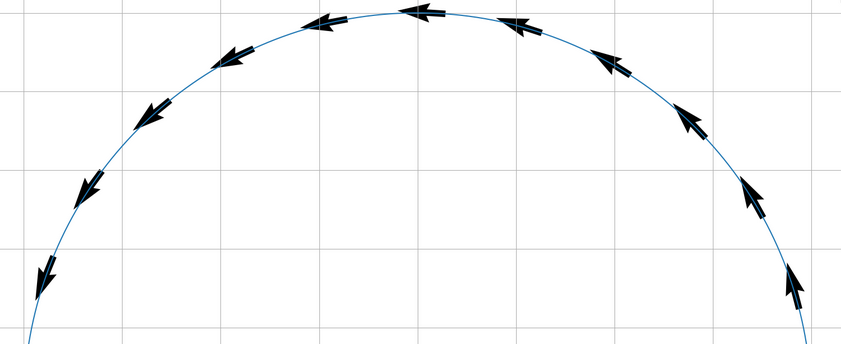

We would like to extend this notion to any regular curve. To do so, given \(\gamma:I\to\mathbb{R}^{2}\) and \(t_{0}\in I\), how can we define the curvature of \(\gamma\) at \(t_{0}\) using circles? We will try to best approximate \(\gamma\) locally by some circle that goes through \(\gamma(t_{0})\).

To simplify our computations, let’s assume that \(t_{0}=0\), \(\gamma(0)=(0,0)\), \(\gamma'(0)=(1,0)\). By (iii) of Definition/Proposition Definition/Proposition 1 \(\gamma''(0)\) is orthogonal to \(\gamma'(0)\) so there exists \(\kappa\in\mathbb{R}\) such that \(\gamma''(0)=(0,-\kappa)\). Furthermore, if we suppose that \(\gamma\) is behaving locally like a circle parameterized in the counter-clockwise direction, we know that \(\kappa>0\).

\(\gamma'(0)=(1,0)\) is drawn in black, \(\gamma''(0)=(0,-\kappa)\) in drawn red and the circle we’re looking for is drawn in orange.

For our circle to be tangent to \((0,1)\) at \((0,0)\) we know that it center must lies on the x-axis so it must be parametrized by \(t\to(x_{C}+R\cos(\dfrac{t}{R}),R\sin(\dfrac{t}{R}))\). Evaluating at \((0,0)\) yields \(x_{C}=-R\) so let \(\gamma_{R}(t)=(-R+R\cos(\dfrac{t}{R}),R\sin(\dfrac{t}{R}))\).

We already have \(\gamma_{R}(0)=\gamma(0)\) and \(\gamma_{R}'(0)=\gamma'(0)\) and the condition \(\gamma_{R}''(0)=\gamma''(0)\) yields \(\dfrac{1}{R}=\kappa\) : the curvature at \(t=0\) is the inverse of the radius of its osculating circle.

For a general unit-speed parametrized curve \(\gamma=(\gamma_{x},\gamma_{y})\) we could carry complicated computations around notice something crucial : curvature is an isometric invariant which means that if \(\phi : \mathbb{R}^{2}\to\mathbb{R}^{2}\) is an isometry that is a map preserving distances then the curvature of \(\phi\circ\gamma\) at \(t=t_{0}\) should be the same as \(\gamma\) at \(t=t_{0}\).

Definition/Proposition 2. A map \(\phi:\mathbb{R}^{n}\to\mathbb{R}^{n}\) is called an isometry if it satisfies \(\lVert\phi(y)-\phi(x)\rVert=\lVert y-x\rVert\quad\forall(x,y)\in\mathbb{R}^{n}\times\mathbb{R}^{n}\).

Every isometry is affine : there exists \(A\in O(n)\) and \(b\in\mathbb{R}^{n}\) such that \(\phi(x)=Ax+b\).

Proof. Left as an exercice :

Consider an isometry \(\phi\) such that \(\phi(0)=0\).

Show that \(\langle\phi(x),\phi(y)\rangle=\langle x,y\rangle\).

Show that \(\phi\) is linear.

Conclude.

◻

If we could transform \(\gamma\) through an isometry to \(\widetilde{\gamma}\) satisfying the previous properties, it would be possible to compute its curvature at \(t=t_{0}\) by looking at the first component of \(\widetilde{\gamma}''(t_{0})\)

Let’s write \(\gamma_{x}\) (resp. \(\gamma_{y},\gamma_{x}',\gamma_{y}',\gamma_{x}'',\gamma_{y}''\)) for \(\gamma_{x}(0)\) (resp. \(\gamma_{y}(t_{0}),\gamma_{x}'(t_{0}),\gamma_{y}'(t_{0}),\gamma_{x}''(t_{0}),\gamma_{y}''(t_{0})\)).

We’re looking for \(A\in O(2)\) and \(b\in\mathbb{R}^{2}\) such that \(\widetilde{\gamma}=A\gamma+b\) satisfies

\[\widetilde{\gamma}(0)=A\begin{pmatrix}\gamma_{x} \\ \gamma_{y}\end{pmatrix}+b=\begin{pmatrix}0 \\ 0\end{pmatrix}\]

\[\widetilde{\gamma}'(0)=A\begin{pmatrix}\gamma_{x}' \\ \gamma_{y}'\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}0 \\ 1\end{pmatrix}\]

(i) forces \(b=-A\begin{pmatrix}\gamma_{x} \\ \gamma_{y}\end{pmatrix}\) while (ii) forces \(B=A^{-1}\) to send \(\begin{pmatrix}

0 \\

1

\end{pmatrix}\) to \(\begin{pmatrix}

\gamma_{x}' \\

\gamma_{y}'

\end{pmatrix}\).

We set \[B=\begin{pmatrix}

\gamma_{y}' &\gamma_{x}'\\

-\gamma_{x}'&\gamma_{y}'

\end{pmatrix}\in O(2)\] so that

\[A=\begin{pmatrix} \gamma_{y}' &-\gamma_{x}'\\ \gamma_{x}'&\gamma_{y}' \end{pmatrix}\in O(2)\]

We know that \(\widetilde{\gamma}''(0)=\begin{pmatrix} -\kappa \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\) with \(\kappa\) its curvature at \(t=0\) which is the same as the curvature of \(\gamma\) so

\[\begin{pmatrix} -\kappa \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}=\widetilde{\gamma}''(0)=A\gamma''(0)=\begin{pmatrix} \gamma_{y}' &-\gamma_{x}'\\ \gamma_{x}'&\gamma_{y}' \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \gamma_{x}''\\ \gamma_{y}'' \end{pmatrix}\]

which gives \[\kappa=\gamma_{x}'\gamma_{y}''-\gamma_{y}'\gamma_{x}''=\det(\gamma',\gamma'')\].

Observe that the second coordinate equality \(\gamma_{x}'\gamma_{x}''+\gamma_{y}'\gamma_{y}''=0\) is true because \(\gamma\) is unit-speed so \(\langle\gamma',\gamma''\rangle=0\).

If \(\kappa\leq0\), which corresponds to the case \(\det(\gamma',\gamma'')<0\) , then \(\widetilde{\gamma}\) behaves locally as a circle going in the clockwise direction. We may apply a symmetry with respect to the y-axis. That is replace \(A\) by \[\begin{pmatrix}

-1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}A=\begin{pmatrix}

-1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}

-\gamma_{y}' &\gamma_{x}'\\

\gamma_{x}'&\gamma_{y}'

\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}

\gamma_{y}' &-\gamma_{x}'\\

\gamma_{x}'&\gamma_{y}'

\end{pmatrix}\in O(2)\]. This is an orientation reversing isometry and \(R=-\dfrac{1}{\det(\gamma',\gamma'')}\)

To sum up :

Definition/Proposition 3. Let \(\gamma\) be a unit speed curve, then \(\kappa(t)\), it’s signed curvature \(\kappa(t)\) at \(\gamma(t)\), is given by \[\det(\gamma'(t),\gamma''(t))\].

We have \(|\kappa(t)|=|\det(\gamma'(t),\gamma''(t)|=\lVert\gamma'(t)\|\) since \(\lVert\gamma'(t)\rVert=1\) and \(\langle\gamma'(t),\gamma''(t)\rangle=0\). This quantity also equals to \(\dfrac{1}{R}\) where \(R\) is the radius of the osculating circle at \(\gamma(t)\) whenever it’s non zero..

To sum up :

We firstly thought curvature as how much the derivative of a curve changes, we noticed how the parametrization might affect this quantity and the relevance of a unit-speed one.

We saw that the curvature of the circle is the inverse of its radius.

We computed the radius of an osculating circle at a point on a curve.

We proved that it’s equal to the inverse of the absolute value of the second derivative when the curve is parametrized by arclength.

Notice that the signed curvature does depend on the unit speed parameterization : changing \(\gamma(t)\) to \(\gamma(-t)\) turns \(\kappa(t)\) to \(-\kappa(t)\) but the absolute value\(|\kappa(t)|=\dfrac{1}{R}\) is well defined independently of the parameterization.

Curvature in two dimensions

Just like curves, we need to specify what we mean by a "surface".

Definition 2. A surface \(\Sigma\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) is the image of a smooth injective map \(\sigma : U_{\Sigma} \to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) with \(U_{\Sigma}\subset\mathbb{R}^{2}\) an open connected subset that is a homeomorphism onto its image and such that \(d\sigma_{x} : \mathbb{R}^{2}\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) is injective (has rank 2) at all points \(x\in U_{\Sigma}\).

We say that \(\sigma\) is a parameterization of \(\Sigma\).

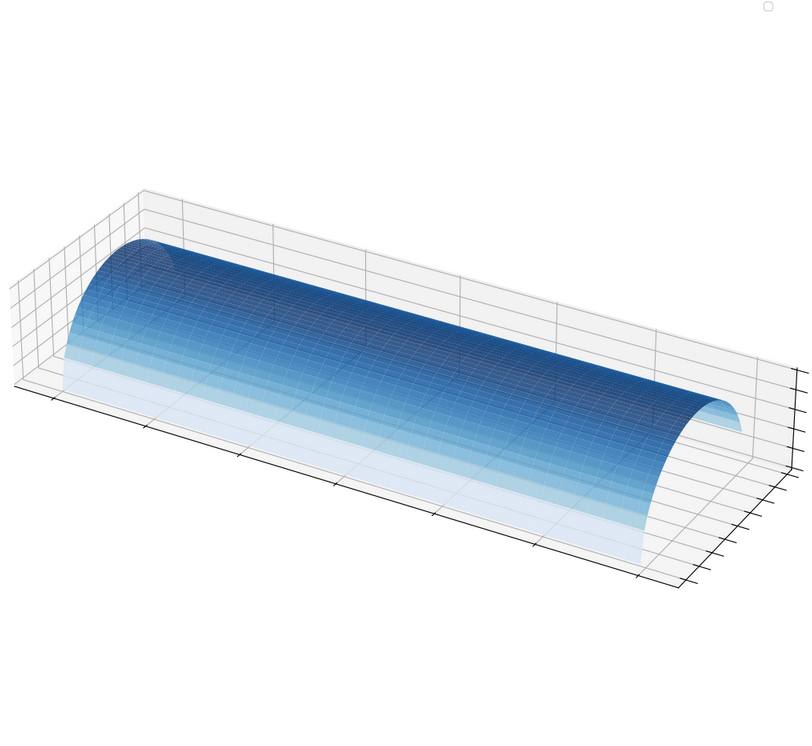

Graph of smooth maps from \(\mathbb{R}^{2}\to\mathbb{R}\) provides us with a lot of interesting examples, below is a portion of the graph of \((x,y)\in\mathbb{R}^{2}\to(x, y, x^{2}-y^{2})\in\mathbb{R}^{3}\)

A big difference that arises when studying surfaces is that, at a given point, the surface may curve in a whole circle of directions. Let’s look at the point \(p=\sigma(0,0)=(0,0,0)\) and visualize different curves going through \(p\).

When we looked at one dimensional curves, we saw that that arclength parametrization gave an acceleration that is orthogonal to the velocity at every point hence encoding the curvature of the object.

The thing is, in two dimensions, even a unit-speed curve in \(\Sigma\) may have an acceleration that is not orthogonal to the surface and have a tangential component. It turns out that curves whose acceleration is everywhere orthogonal to the surfaces are fundamental objects in Riemannian geometry : these are the geodesics.

A random curve in green and a geodesic in red

A remarkable property is that these curves are also, at least locally, length minimizing. Actually, the two are equivalent and this is how they are introduced in most books.

To give a precise meaning to what we mean by "orthogonal to the surface", it is time to introduce \(T_{p}\Sigma\) the tangent space of \(\Sigma\) :

Definition/Proposition 4. The tangent space \(T_{p}\Sigma\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) is the collection of all vectors that can be realized as \(\gamma'(0)\) with \(\gamma : I\to\Sigma\) a smooth curve satisfying \(\gamma(0)=p\).

It is a 2 dimensional linear subspace.

Different tangent spaces

Definition/Proposition 5. A smooth curve \(\gamma : I\to\Sigma\) that satisfies \(\gamma''(t)\in (T_{\gamma(t)}\Sigma)^{\perp}\) is called a geodesic.

A geodesic has (not necessarily unit) constant speed.

For any points \((p,q)\in\Sigma^{2}\) the shortest path in \(\Sigma\) between \(p\) and \(q\) is a geodesic.

Every geodesic is locally a shortest path : for any \(t_{0}\in I\) there is \(\epsilon>0\) such that \(\forall(t_{1},t_{2})\in]t_{0}-\epsilon,t_{0}+\epsilon[^{2}\) with \(t_{1}<t_{2}\): \(\gamma_{|[t_{1},t_{2}]}\) is the shortest path between \(\gamma(t_{1})\) and \(\gamma(t_{2})\)

Proof.

Let \(f(t)=\lVert\gamma'(t)\|^{2}\) then \(f'(t)=2\langle\gamma'(t),\gamma''(t)\rangle=0\) because \(\gamma'(t)\in T_{\gamma(t)}\Sigma\) and \(\gamma''(t)\in (T_{\gamma(t)}\Sigma)^{\perp}\) so \(f\) is constant.

We will only prove the following : assume that the shortest path between \(p\) and \(q\) exists and is a smooth curve, then it must be a geodesic.

Let \(\gamma:[a,b]\to\Sigma\) be the shortest path between \(p=\gamma(a)\) and \(q=\gamma(b)\) parametrized by arclength and let \(\Gamma : I\times J\to\Sigma\) be any smooth map with \(J\subset \mathbb{R}\) an interval such that \(\Gamma(.,0)=\gamma\), \(\Gamma(a,.)=p\) and \(\Gamma(b,.)=q\). In other words, \(\Gamma\) is a collection of paths \(\Gamma(s,.):=\gamma_{s}\) from \(p\) to \(q\) parametrized by \(J\). We assume furthermore that each \(\gamma_{s}\) satisfies \(\gamma_{s}'(t)\neq 0\) for all \(t\in J\).

Since \(\gamma\) is the shortest path, the functional \(F:J\to\mathbb{R}=\int_{a}^{b}\lVert\gamma'_{s}(t)\rVert dt=\int_{a}^{b}\lVert\dfrac{\partial\Gamma(t,s)}{\partial t}\rVert dt\) has a minimum at 0 and hence its derivative must vanish.

Let’s compute \[F'(s)=\dfrac{d}{ds}\int_{a}^{b}\lVert\gamma_{s}'\rVert=\dfrac{d}{ds}\int_{a}^{b}\sqrt{\langle \dfrac{\partial \Gamma}{\partial t}(s,t),\dfrac{\partial \Gamma}{\partial t}(s,t)\rangle}dt\] \[=\int_{a}^{b}2\langle\dfrac{\partial^{2}\Gamma}{\partial s\partial t}(s,t),\dfrac{\partial \Gamma}{\partial t}(s,t)\rangle\dfrac{1}{2\sqrt{\langle \dfrac{\partial \Gamma}{\partial t}(s,t),\dfrac{\partial \Gamma}{\partial t}(s,t)\rangle}}dt\]Evaluating at \(s=0\) and observing that \(\sqrt{\langle \dfrac{\partial \Gamma}{\partial t}(0,t),\dfrac{\partial \Gamma}{\partial t}(0,t)\rangle}=\sqrt{\langle \gamma'(t),\gamma'(t)\rangle}=1\) we have :

\[\int_{a}^{b}\langle\dfrac{\partial^{2}\Gamma}{\partial s\partial t}(0,t),\gamma'(t)\rangle dt=0\]

Let \(X:I\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) be defined by \(X(t)=\dfrac{\partial\Gamma}{\partial s}(0,t)\).

\(X(t)\in T_{\gamma(t)}\Sigma\) as the derivative of \(\Sigma\)-valued map \(s\to\Gamma(s,t)\).

\(X(a)=X(b)=0\) because \(\Gamma(s,a)=p\) and \(\Gamma(s,b)=q\) for all \(s\in J\).

The last equation becomes \[F'(0)=\int_{a}^{b}\langle X'(t),\gamma'(t)\rangle dt\] and integration by parts yields \[F'(0)= \langle X(b),\gamma'(b)\rangle-\langle X(a),\gamma'(a)\rangle -\int_{a}^{b}\langle X(t),\gamma''(t)\rangle dt=0\] so that \(F'(0)=-\int_{a}^{b}\langle X(t),\gamma''(t)\rangle dt=0\).

Now if there were some \(t_{0}\in I\) such that \(\gamma''(t_{0})\notin (T_{\gamma(t_{0})}\Sigma)^{\perp}\) we could find \(X_{0}\in T_{\gamma(t)}\Sigma\) such that \(\langle X_{0},\gamma''(t_{0})\rangle>0\) then build a vector field \(X\) tangent to \(\Sigma\) along \(\gamma\) such that \(\langle X(t)\,\gamma''(t)\rangle\geq0\) and \(\langle X(t_{0})\,\gamma''(t_{0})\rangle>0\) so that \(\int_{a}^{b}\langle X(t),\gamma''(t)\rangle dt>0\). Finally, we can find \(\Gamma\) such that \(X(t)=\dfrac{\partial\Gamma}{\partial s}(0,t)\) so that \(F'(0)<0\) which is a contradiction.

◻

The proof also tells us how to modify a curve to decrease its length : me must bend it around a point in the direction of its acceleration at that point which is quite intuitive.

Moving the curve in the acceleration (red) direction decreases the length.

Before going back to curvatures, let’s see if geodesics actually do exist and how can we compute them. At each point \(p\in\Sigma\) the tangent space \(T_{p}\Sigma\) is a 2 dimensional linear subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\) and \((T_{p}\Sigma)^{\perp}\) is a vectorial line.

Given a parameterization of the surface \(\sigma\) it’s actually easy to compute a vector spanning this one dimensional subspace : let \(\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial x}\) and \(\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial y}\) the directional derivatives of \(\sigma\) at \(p\) then the vectorial product \(\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial x}\wedge\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial y}\) is a non zero element of \((T_{p}\Sigma)^{\perp}\), we note \(N(p)\) or \(N_{p}\) the associated normalized vector.

We talked about smooth vector fields along a curve in \(\mathbb{R}^{2}\) or \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\). There is an analogous concept for surfaces that we precise in the following definition :

Definition 3. Let \(\Sigma\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) be a surface parametrized by \(\sigma : U_{\Sigma}\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\).

A vector field along \(\Sigma\) is a map \(X:\Sigma\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) such that the composite \(X\circ\sigma:U_{\Sigma}\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) is a smooth map. We often write \(X_{p}\) instead of \(X(p)\) for \(p\in\Sigma\)

Given \(p\in\Sigma\) and \(v\in T_{p}\Sigma\), we define \(\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial v}(p)\) the derivative of \(X\) at \(p\) in the \(v\)-direction as the derivative of \(X\circ\gamma\) at \(0\) for \(\gamma : I\to\Sigma\) being any curve satisfying \(\gamma(0)=p\) and \(\gamma'(0)=v\).

Notice that this makes sense only for tangent vector \(v\) as the vector field \(X\) is only defined on \(\Sigma\).

A vector field tangent to \(\Sigma\) is a vector field along \(\Sigma\) \(X\) such that \(X_{p}\in T_{p}\Sigma\quad\forall p\in\Sigma\).

\(\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial x}\) in green, \(\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial y}\) in red and \(N\) in purple

By construction, \(\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial x}\) and \(\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial y}\) are vector fields tangent to \(\Sigma\) and \(N\) is a vector field along \(\Sigma\).

The orthogonal projection on \(T_{p}\Sigma\) reads \(v\to v-\langle v,N_{p}\rangle N_{p}\) so that \(\gamma\) is a geodesic iff \(\gamma''(t)-\langle \gamma''(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle N_{\gamma(t)}=0\iff \gamma''(t)=\langle \gamma''(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle N_{\gamma(t)}\).

Since \(\gamma\) is \(\Sigma\)-valued we have \(\gamma'(t)\in T_{\sigma(t)}\Sigma\) and \(\langle \gamma'(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle=0\). Differentiating the last expression yields \(0=\langle\gamma''(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle+\langle\gamma'(t),N'_{\gamma(t)}\rangle\) with \(N'_{\gamma(t)}\) is understood as the derivative of \(t\to N_{\gamma(t)}\) and the geodesic equation becomes \[\gamma''(t)=-\langle\gamma'(t),N'_{\gamma(t)}\rangle N_{\gamma(t)}\].

The normal vector field along a geodesic.

So \(\gamma\) is a geodesic going through \(p\in \Sigma\) with initial speed \(v\in T_{p}\Sigma\) iff it solves the second order linear differential equations : \[\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \gamma(0)=p \\ \gamma'(0)=v \\ \gamma''(t)=-\langle\gamma'(t),N'_{\gamma(t)}\rangle N_{\gamma(t)} \end{array} \right.\]

There is a problem though : a proper second order autonomous differential equation in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\) must be written \[\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \gamma(0)=p \\ \gamma'(0)=v \\ \gamma''(t)=F(\gamma(t),\gamma'(t)) \end{array} \right.\]

with \(F\) defined on an open subset of \(\mathbb{R}^{6}\) containing \((p,v)\).

We are tempted to define \(F(p,v)=-\langle v,\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial v}(p)\rangle N_{p}\). Unfortunately, \(F\) is not defined on \(\mathbb{R}^{6}\) but only on \[T\Sigma:=\{(p,v)\in\Sigma\times\mathbb{R}^{3}\quad| \quad v\in T_{p}\Sigma\}\] the tangent bundle of \(\Sigma\) (we will study this object in depth in the next section when introducing abstract manifolds).

Now we can circumvent this problem by extending \(N\) smoothly on an open subset \(V\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) containing \(\Sigma\) and define \(F:V\times \mathbb{R}^{3} \to \mathbb{R}^{3}\) by \(F(p,v)=-\langle v,\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial v}(p)\rangle N_{p}\) yielding a true solution \(\gamma : I\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) with \(I\) an open interval containing \(0\).

Sadly, we traded one problem for another : why would \(\gamma\), a curve solving an ODE in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\), take its values in the 2 dimensional surface \(\Sigma\)?

We won’t prove rigorously that it actually does but observe the following : \(q(t):=\langle \gamma'(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle\) is well defined near \(0\) and verifies \(q(0)=\langle \gamma'(0),N_{\gamma(0)}\rangle=\langle v,N_{p}\rangle=0\) and \[q'(t)=\langle \gamma''(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle+\langle \gamma'(t),N'_{\gamma(t)}\rangle=-\langle\gamma'(t),N'_{\gamma(t)}\rangle\langle N_{\gamma(t},N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle+\langle\gamma'(t),N'_{\gamma(t)}\rangle=0\] so that \(q(t)\equiv0\) on its domain of definition. It means that \(\gamma(0)\) belongs to \(\Sigma\) and is orthogonal to \(N\) near \(0\) which is a good hint that it should lie in \(\Sigma\) around \(p\).

We are finally ready to express the curvature of \(\Sigma\) at \(p\) in the \(v\) direction : recall that, as in the one dimensional case, it should be equal to \(\pm\rVert\gamma''(0)\rVert\). Being a geodesic, \(\gamma''(0)=-\langle \gamma'(0),N'_{\gamma(0)}\rangle N_{\gamma(0)}\) but \(N\) being unit everywhere, the desired quantity is \(\pm|\langle v,\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial v}(p)\rangle|\) which motives the following definition :

Definition 4. Let \(\Sigma\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) be a surface, \(N\) a normal unit vector field along \(\Sigma\) and \(p\in\Sigma\).

We define \(\mathbb{I}_{p}\), the second fundamental form at p with respect to \(N\), as the following bilinear form on \(T_{p}\Sigma\) by \(\mathbb{I}_{p}(v,w)=\langle v,\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial w}(p)\rangle\).

It turns out that this form is symmetric but before proving it, we need to introduce a key differential geometric concept : the Lie brackets of two vector fields. It may not be intuitive at first glance but we’ll have the opportunity to study it more thoroughly when needed.

Definition/Proposition 6. Let \(X,Y\) be vector fields tangents to \(\Sigma\). Just let \(\dfrac{\partial Y}{\partial X}\) (resp.\(\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial Y}\)) be the vector field along \(\Sigma\) whose value at \(p\) is \(\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial Y_{p}}\) (resp. \(\dfrac{\partial Y}{\partial X_{p}}\)). Notice that these need not to be tangent to \(\Sigma\).

The Lie bracket \([X,Y]\) of \(X\) and \(Y\) is defined by \(\dfrac{\partial Y}{\partial X}-\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial Y}\), it is a tangent vector field on \(\Sigma\) : \([X,Y]_{p}\in T_{p}\Sigma\quad\forall p\in\Sigma\).

Proposition 1. The second fundamental form \(\mathbb{I}\) induces a symmetric bilinear form on \(T_{p}\Sigma\) at every point \(p\in\Sigma\).

Proof. Let \(p\in\Sigma\) and \((v,w)\in T_{p}\Sigma^{2}\).

Let \(\gamma_{1} : I\to\Sigma\) (resp. \(\gamma_{2} : I\to\Sigma\)) such that \(\gamma_{1}(0)=p\) (resp. \(\gamma_{2}(0)=p\)) and \(\gamma_{1}'(0)=v\) (resp. \(\gamma_{2}'(0)=w\)).

Let \(X\) (resp. \(Y\)) a vector field tangent to \(\Sigma\) such that \(X_{p}=v\) (resp. \(Y_{p}=w\)).

The function \(q_{1}:I\to\mathbb{R}\) defined by \(q_{1}(t)=\langle Y_{\gamma_{1}(t)},N_{\gamma_{1}(t)}\rangle\) is constant equals to \(0\) since \(Y\) is tangent to \(\Sigma\) at every point. By derivating \(q_{1}\) and evaluating in \(t=0\) we get \[0=\langle \dfrac{\partial Y}{\partial v}(p),N_{p}\rangle+\langle w,\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial v}(p)\rangle\] or \(\mathbb{I}_{p}(w,v)=-\langle \dfrac{\partial Y}{\partial v}(p),N_{p}\rangle=-\langle \dfrac{\partial Y}{\partial X}(p),N_{p}\rangle\).

Similarly, by defining \(q_{2}(t)=\langle X_{\gamma_{2}(t)},N_{\gamma_{2}(t)}\rangle\) we get \(\mathbb{I}_{p}(v,w)=-\langle \dfrac{\partial X}{\partial Y}(p),N_{p}\rangle\).

Substracting the two we get \[\mathbb{I}_{p}(w,v)-\mathbb{I}_{p}(v,w)=\langle-\dfrac{\partial Y}{\partial X}(p)+\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial Y}(p),N_{p}\rangle=-\langle [X,Y]_{p} ,N_{p}\rangle=0\] since \([X,Y]\) is tangent to \(\Sigma\). ◻

Also, we deduce from the proof the following interesting facts : given \(X\) and \(Y\) two tangent vector fields on \(\Sigma\) the value \(\mathbb{I}_{p}(X_{p},Y_{p})=-\langle \dfrac{\partial Y}{\partial X}(p),N_{p}\rangle\) depends only on the pointwise value of \(X\) and \(Y\) at \(p\) which is not clear at first glance since this expression involves the derivative of \(Y\) along \(X\).

For each \(p\in\Sigma\) we have a symmetric form on \(T_{p}\Sigma\) with the induced ambient scalar product of \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\). Since by definition \(\mathbb{I}_{p}(v,w)=\langle v,\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial w}(p)\rangle\) we deduce that the associated symmetric operator on \(T_{p}\Sigma\) is \(w\to\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial w}(p)\).

It must be equal to the orthogonal projection of \(\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial w}(p)\) on \(T_{p}\Sigma\) but since \(N\) is unit we have \(0=\dfrac{\partial \lVert N\rVert^{2}}{\partial w}=2\langle\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial w},N\rangle\) so that \(\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial w}(p)\in N_{p}^{\perp}=T_{p}\Sigma\).

Definition 5. For \(p\in\Sigma\), let \(s_{p}\) be the operator on \(T_{p}\Sigma\) defined by \(s_{p}(w)=\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial w}(p)\).

The operator \(s_{p}\) is symmetric for the scalar product induced on \(T_{p}\Sigma\) by the ambient euclidian space and verifies \(\mathbb{I}_{p}(v,w)=\langle v,s_{p}(w)\rangle\).

Its eigenvalues are called the principal curvatures of \(\Sigma\) at \(p\) and the corresponding eigenspaces are called the principal directions.

The product of the eigenvalues, that is the determinant of \(s_{p}\) or \(\mathbb{I}_{p}\) in any orthonormal basis, is called the Gaussian curvature of \(\Sigma\) at \(p\).

In conclusion, the intensity with which the surface curves in a direction is measured by the quadratic form \(\mathbb{I}_{p}\) which is best described by the eigenvalues of the associated symmetric operator.

Note that if \(N\) is a normal vector then so is \(-N\) and the second fundamental form, the shape operators and the principal curvatures are multiplied by \(-1\) which suggests that these objects are not intrinsically defined neither. We had the same problem for one dimensional curves in the plane, reversing the orientation of the curve changes the sign of the curvature \(\kappa(t)\).

Let’s try to compute it explicitly for a very broad class of surfaces : graph of maps from an open subset of the plane to \(\mathbb{R}\) : given a open subset \(U\subset\mathbb{R}^{2}\) and a smooth map \(f:U\to\mathbb{R}\) let \(\sigma : U\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) be defined by \(\sigma(x,y)=(x,y,f(x,y))\) and let \(\Sigma:=\sigma(U)\).

Let \((x_{0},y_{0})\) be a critical point of \(f\) i.e. such that \(\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_{0},y_{0})=\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_{0},y_{0})=0\) and let \(p_{0}=(x_{0},y_{0},f(x_{0},y_{0}))\in\Sigma\) so that \(T_{p}\Sigma\) is the horizontal plane. We will see later that this not a big loss of generality.

It is easy to derive an orthogonal vector along \(\Sigma\) : at every point \(p\in\Sigma\) the tangent space \(T_{p}\Sigma\) is spanned by \(\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial x}=\begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} \end{pmatrix}\) and \(\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial y}=\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} \end{pmatrix}\) and we see that \(\widetilde{N}=\begin{pmatrix} -\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} \\ -\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} \\ 1\end{pmatrix}\) is orthogonal to both so that \(N:=\dfrac{\widetilde{N}}{\lVert\widetilde{N}\rVert}\) is a normal vector for \(\Sigma\).

It looks way easier to differentiate \(\widetilde{N}\) instead of \(N\) : the good news is that their derivative match at \(p\). Indeed, define \(\lambda:\Sigma\to\mathbb{R}\) by \(\lambda(p)=\dfrac{1}{\lVert N_{p}\rVert}\). We see that \(\lambda\) is smooth as \((\lambda\circ\sigma)(x,y)=\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1+(\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x}) ^{2}+(\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y})^{2}}}\) and we can write \(N=\lambda\widetilde{N}\).

Moreover this expression can be obtained as the composite of \(z\to\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1+z}}\) with \((x,y)\to (\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x}) ^{2}+(\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y})^{2}\) whose derivatives vanish at \((x_{0},y_{0})\), we conclude that the derivatives of \(\lambda\) also vanish at that \(p\) and \(\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial w}(p)=\dfrac{\partial (\lambda\widetilde{N})}{\partial w}(p)=\dfrac{\partial \lambda}{\partial w}(p)N(p)+\lambda(p)\dfrac{\partial \widetilde{N}}{\partial w}(p)=\dfrac{\partial \widetilde{N}}{\partial w}(p)\).

It is now very easy to compute the second fundamental form : given a vector \(v\in T_{p}\Sigma\) then \(s_{p}(v)\) is obtained by differentiating \(\widetilde{N}\) and dropping the last coordinate. In the orthogonal basis \(\{e_{1},e_{2}\}\) of \(T_{p}\Sigma\) with \(e_{1}=(1,0,0)=\dfrac{\partial\sigma}{\partial x}(x_{0},y_{0})\) and \(e_{2}=(0,1,0)=\dfrac{\partial\sigma}{\partial y}(x_{0},y_{0})\) the matrix of \(\mathbb{I}_{p}\) and \(s_{p}\) is given by \[\begin{pmatrix}

-\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial^{2}x} & -\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial x\partial y} \\

-\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial x\partial y} & -\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial^{2}y}

\end{pmatrix}\] which is no less than the opposite of the Hessian of \(f\) at \((x_{0},y_{0})\).

The figure below show the principal directions for \(f:(x,y)\to x^{2}-y^{2}\) at \(p=(0,0,0)\). The Hessian is given \[\begin{pmatrix}

1 & 0\\

0 & -1

\end{pmatrix}\] and we have two principal directions in which \(\Sigma\) curve in opposite ways.

Just as we did for one dimensional curve we can compute the second fundamental form at any point \(p\in \Sigma\) by choosing an isometry of \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\) that fixes \(p\) and maps \(T_{p}\Sigma\) to the horizontal plane. Around \(p\), the new surface may be described as the graph of a function with a critical point and the principal curvatures may be retrieved by computing the Hessian.

Isometries between surfaces in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\)

It is the second time we use isometries to simplify our computations. We did so because we intuitively think of curvature as an isometric invariant. The isometries of the plane and the space are generated by translations, rotations and symmetries which do not distort our surfaces and hence preserve curvature.

Just as is many areas of mathematics, we wish to find invariants that are preserved by structure-preserving maps. In Riemannian geometry, the preserved structure is the distance between points. The bad news is that the principal curvatures (even modulo multiplication by \(-1\)) are not an isometric invariant but the good news is that the Gaussian curvature is as we shall see.

We already talked about distances between points on surfaces when we studied geodesics : the distance between two points is the shortest length of smooth paths connecting the two points. For a surface \(\Sigma\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\), we define a distance \(d\) as the infimum length of smooth \(\Sigma\)-valued path between \(p\) : \[d(p,q)=\inf\{\mathop{\mathrm{Length}}(\gamma)\quad|\quad \gamma\in C^{\infty}([0,1],\Sigma) \quad s.t. \gamma(0)=p,\quad \gamma(1)=q\}\]. It can be proved that the infimum is actually a minimum reached on a geodesic and that \(d\) is a proper distance that turns \(\Sigma\) into a metric space whose induced topology coincide with the subset topology.

Before precising what "equivalent" means from a Riemannian perspective, we need to do it from a differential geometric one :

Definition/Proposition 7. Let \(\Sigma_{1}=\sigma_{1}(U_{1})\) and \(\Sigma_{2}=\sigma_{2}(U_{2})\) be two parametrized surfaces. A map \(\phi : \Sigma_{1}\to\Sigma_{2}\) is called smooth if \(\phi\circ\sigma_{1}\) is smooth as a map into \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\).

For such a map, let \(p\in\Sigma_{1}\) and \(v\in T_{p}\Sigma_{1}\) and define \(d\phi_{p}:T_{p}\Sigma_{1}\to T_{\phi(p)}\Sigma_{2}\) as \(\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}\phi\circ\gamma(t)\) with \(\gamma: I\to\Sigma_{1}\) be any smooth curve from an interval \(I\) containing \(0\) that verifies \(\gamma(0)=p\) and \(\gamma'(0)=v\). This is the differential of \(\phi\) at \(p\) and it is a linear map.

A diffeomorphism between \(\Sigma_{1}\) and \(\Sigma_{2}\) is a smooth bijection whose inverse is also smooth.

Two surfaces are said to be diffeomorphic is there exists a diffemorphism between them.

Now, taking account the metric structure :

Definition 6. Let \(\Sigma_{1}=\sigma_{1}(U_{1})\) and \(\Sigma_{2}=\sigma_{2}(U_{2})\) be two parametrized surfaces and \(d_{1}\) and \(d_{2}\) their metric distances.

A map \(\phi : \Sigma_{1}\to\Sigma_{2}\) is called a smooth isometry if

it is a diffemorphism between \(\Sigma_{1}\) and \(\Sigma_{2}\).

it is a metric isometry that is, for all \((p,q)\in\Sigma_{1}\) : \(d_{2}(\phi(p),\phi(q))=d_{1}(p,q)\).

There is a more algebraic way to characterize smooth isometries.

Proposition 2. Let \(\Sigma_{1}=\sigma_{1}(U_{1})\) and \(\Sigma_{2}=\sigma_{2}(U_{2})\) be two parametrized surfaces and \(\phi : \Sigma_{1}\to\Sigma_{2}\) be a map satisfying (i) and (ii) from definition Definition 6.

Then \(\phi\) is a smooth isometry iff for all \(p\in\Sigma_{1}\) the differential \(d\phi_{p} : T_{p}\Sigma_{1}\to T_{\phi(p)}\Sigma_{2}\) is a euclidean isomorphism between the two tangent spaces equipped with the ambient scalar product, i.e. it satisfies for all \((v,w)\in T_{p}\Sigma_{1}^{2}\) : \[\langle d\phi_{p}(v),d\phi_{p}(w)\rangle=\langle v,w\rangle\].

Proof.

Let \((p,q)\in \Sigma_{1}^{2}\) and \(\gamma : [a,b]\to\Sigma_{1}\) the shortest path between \(p\) and \(q\) (hence a geodesic). Then \(\phi\circ\gamma\) is a path between \(\phi(p)\) and \(\phi(q)\) with length

\[\int_{a}^{b}\lVert(\phi\circ\gamma)'(t)\rVert^{2}dt=\int_{a}^{b}\lVert d\phi_{\gamma(t)}(\gamma('t))\rVert^{2}dt=\int_{a}^{b}\lVert(\gamma'(t)\rVert^{2}dt=\mathop{\mathrm{Length}}(\gamma)\] so that \(d_{2}(\phi(p),\phi(q))\leq d_{1}(p,q)\).

Now \(\phi^{-1}\) satisfies the same conditions as \(\phi\) and we conclude that \(d_{2}(\phi(p),\phi(q))\geq d_{1}(p,q)\) and \(\phi\) is a metric isometry.

Let \(p\in\Sigma_{1}\), \(v\in T_{p}\Sigma_{1}\) and \(\gamma : ]-\epsilon,\epsilon[\to\Sigma_{1}\) be the restriction of the maximal geodesic going through \(p\) at velocity \(v\) at \(p\) and \(\epsilon\) be small enough such that, for all \((t_{1},t_{2})\) with \(-\epsilon<t_{1}<t_{2}<\epsilon\), \(\gamma_{|[t_{1},t_{2}]}\) is the shortest path between \(\gamma(t_{1})\) and \(\gamma(t_{2})\).

Since \(\phi\) is a metric isometry, \(\phi\circ\gamma\) is also length minimizing and \[\int_{t_{1}}^{t_{2}}\lVert(\phi\circ\gamma)'(t)\rVert dt=d_{2}(\phi(\gamma({t_{1}}),\phi(\gamma(t_{2})))=d_{1}(\gamma(t_{1}),\gamma(t_{2}))=\int_{t_{1}}^{t_{2}}\lVert\gamma'(t)\rVert dt\]

\[\iff \int_{t_{1}}^{t_{2}}\lVert(d\phi_{\gamma(t)}(\gamma'(t))\rVert dt=\int_{t_{1}}^{t_{2}}\lVert\gamma'(t)\rVert dt\]Dividing by \(t_{2}-t_{1}\) and letting \(t_{1},t_{2}\to 0\) we get \(\lVert d\phi_{p}(v)\rVert=\rVert v\rVert\) so that \(\lVert d\phi_{p}(v)\rVert^{2}=\rVert v\rVert^{2}\) and we conclude by polarization.

◻

Since we’re dealing with smooth objects we only introduced smooth metric isometries but we could have also considered general metric isometries : any map between surfaces that preserve distances. It turns out that these maps are automatically smooth making the terminology "smooth isometry" redundant. The proof relies on geodesics properties : a metric isometry is taking shortest paths to shortest paths that is smooth object to other smooth objects. Hence, from now on, we will use the term isometry for any map satisfying the conditions of definition Definition 6.

We are now ready to prove that the second fundamental form is not an isometric invariant (nor its reduction modulo multiplication by \(-1\)) and that we should seek a more intrinsic quantity to measure curvature.

Let \(I\) be any open interval of \(\mathbb{R}\), let \(U=I\times]-\pi,\pi[\) and \(\sigma_{2}:U\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) be defined by \(\sigma_{2}(x,y)=(x,\cos(y),\sin(y))\). The surface \(\Sigma_{2}:=\sigma_{2}(U)\) is a half-cylinder parametrized by the map \(\sigma_{2}\).

Even if \(U\) is already a flat surface as an open subset of \(\mathbb{R}^{2}\) we embed it into \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\) via the map \(\sigma_{1}:(x,y)\to(x,y,0)\) to treat it evenly and denote \(\Sigma_{1}:=\sigma_{1}(U)\).

The map \(\phi:\Sigma_{1}\to\Sigma_{2}\) defined by \(\phi(x,y,0)=\sigma_{2}(x,y)\) is a bijection between \(\Sigma_{1}\) and \(\Sigma_{2}\). The smoothness of \(\phi\), as a map from one surface to another, is due to the smoothness of \(\sigma_{2}\) while the smoothness of \(\phi^{-1}\) is due to the smoothness of \(\sigma_{1}\). To prove that \(\widetilde{\sigma}\) is an isometry we only need to prove that its differential is an euclidean isomorphism at each point.

Now let \(p=(x_{0},y_{0},0)\in\Sigma_{1}\), we will to prove that \(d\phi_{p}\) takes an orthogonal basis to another one. Let \(e_{1}=(1,0,0)\) and \(e_{2}=(0,1,0)\) so that \(\{e_{1},e_{2}\}\) is an orthogonal basis for \(T_{p}\Sigma_{1}\).

The tangent vector \(e_{1}\) (resp. \(e_{2}\)) can be seen as the derivative at \(t=0\) of \(\gamma_{1}(t)=(x+t,y,0)\) (resp. \(\gamma_{2}(t)=(x,y+t,0)\)) so that \[\widetilde{e_{1}}:=d\phi_{p}(e_{1})=\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}\phi(\gamma_{1}(t))=\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}\begin{pmatrix}x+t \\ \cos(y) \\ \sin(y)\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0\end{pmatrix}\] and

\[\widetilde{e_{2}}:=d\phi_{p}(e_{2})=\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}\phi(\gamma_{1}(t))=\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}\begin{pmatrix}x \\ \cos(y+t) \\ \sin(y+t)\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ -\sin(y) \\ \cos(y)\end{pmatrix}\]

The basis \(\{\widetilde{e_{1}},\widetilde{e_{2}}\}=\{d\phi_{p}(e_{1}),d\phi_{p}(e_{2})\}\) is orthonormal and \(\phi\) is an isometry between \(\Sigma_{1}\) and \(\Sigma_{2}\).

This shows that, to the eyes of a Riemannian geometer, the half cylinder is surprisingly flat, being isometric to a rectangle.

Some geodesics on the rectangle and their images in the half-cylinder

Let’s take a look at the second fundamental forms of \(\Sigma_{1}\) and \(\Sigma_{2}\).

The constant vector \(N_{1}:\Sigma_{1}\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) defined by \(N_{1}(p)=(0,0,1)\) is a normal vector for \(\Sigma_{1}\) which show that its second fundamental form vanishes.

Concerning \(\Sigma_{2}\), we can choose \(N_{2}:\Sigma_{2}\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) defined by \[N_{2}(x,\cos(y),\sin(y))=\begin{pmatrix} 0\\ \cos(y)\\\sin(y))

\end{pmatrix}\] as it is unit and orthogonal to \(\widetilde{e_{1}}\) and \(\widetilde{e_{2}}\).

We compute \[\dfrac{\partial N_{2}}{\partial \widetilde{e_{1}}}=\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}N_{2}(x+t,\cos(y),\sin(y))=\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}\begin{pmatrix} 0\\ \cos(y)\\\sin(y))

\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix} 0\\ 0\\ 0

\end{pmatrix}\] and \[\dfrac{\partial N_{2}}{\partial \widetilde{e_{2}}}=\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}N_{2}(x,\cos(y+t),\sin(y+t))=\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}\begin{pmatrix} 0\\ \cos(y+t)\\\sin(y+t))

\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix} 0\\ -\sin(y)\\ \cos(y)

\end{pmatrix}=\widetilde{e_{2}}\]

and matrix of the second fundamental form is the basis \(\{\widetilde{e_{1}},\widetilde{e_{2}}\}\) reads \(\begin{pmatrix}

0 & 0 \\

0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}\).

Observing that \(\Sigma_{2}\) can also be realized at the graph of \(f:I\times]-1,1[\to\mathbb{R}^{2}\) defined by \(f(x,y)=\sqrt{1-y^{2}}\) we could have also easily computed the second fundamental form at points \((x,y,f(x,y))\) with \((x,y)\) being a critical point of \(f\), that is \(y=0\), by computing the Hessian \[\begin{pmatrix}

-\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial^{2}x} & -\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial x\partial y} \\

-\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial x\partial y} & -\dfrac{\partial^{2}f}{\partial^{2}y}

\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}

0 & 0 \\

0 & -1

\end{pmatrix}\].

We noticed that the second fundamental form can not be defined intrinsically because of the choice of a normal vector among two candidates but the situation is quite different here : one vanishes while the other has always rank 1. Nevertheless notice that, as announced before, the Gaussian curvature, the determinant of \(\mathbb{I}_{p}\) in any orthonormal basis, is zero.

Taking a look back at curves in \(\mathbb{R}^{2}\) with our brand new Riemannian eyes, we also assert the embarrassing but nevertheless true following statement : "every curve is flat". Indeed, every curve is isometric to an interval, the isometry being given by arclength parametrization : given a unit speed curve \(\gamma:I\to\gamma(I)\), \(d\gamma_{\gamma(t)}\) is an euclidean isomorphism between two one dimensional space if and only if \(\lVert\gamma'(t)\rVert=1\).

Why does all of this feel kind of weird? We need to make the crucial distinction between what is intrinsic and extrinsic. We picture surfaces as subset of \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\) but if we want to classify them modulo isometry, we need to study \(\Sigma\) regardless of the way it lies in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\), the only structure we’re interested into is the distance between pair of points.

The second fundamental form is extrinsic in the sense that it depends on the way the surface lies in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\). Nevertheless, it should be invariant under global isometry of \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\). Any such isometry would be affine and therefore can not map the flat rectangle to the half cylinder.

To find intrinsic invariants, we need to treat a surface regardless of its position in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\) while still being able to manipulate algebraic objects such as derivative, tangent spaces, smooth maps, scalar product and so on. This is the motivation of differential geometry that will be introduced in the next section.

Before diving into the wonderful world of differential geometry, we will try to get familiar with the cornerstone of isometric invariants : parallel transport and visualize it of embedded surfaces of \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\).

Parallel transport

We first introduced curvature as the obstruction for a tangent vector field of being constant. Nevertheless, we can relax this condition and ask for a vector field tangent to \(\Sigma\) to have its derivatives lying in \(T_{p}\Sigma^{\perp}\).

Definition 7. Let \(\Sigma\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) be a surface and \(N\) a normal vector field. A vector field \(X\) tangent to \(\Sigma\) is called parallel if \(\forall p\in\Sigma\), \(\forall v\in T_{p}\Sigma\) : \(\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial v}\in T_{p}\Sigma^{\perp}\)

Looking at the half-cylinder \(\Sigma_{2}=\sigma_{2}(U)\) with \(U=I\times]-\pi,\pi[\) and \(\sigma_{2}:U\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) defined by \(\sigma_{2}(x,y)=(x,\cos(y),\sin(y))\) we already computed at \(p=(x,\cos(y),\sin(y))\) : \[\dfrac{\partial \sigma_{2}}{\partial x}(p)=\begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0\end{pmatrix}\] and \[\dfrac{\partial \sigma_{2}}{\partial y}(p)=\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ -\sin(y) \\ \cos(y)\end{pmatrix}\].

\(\dfrac{\partial \sigma_{2}}{\partial x}\) in green and \(\dfrac{\partial \sigma_{2}}{\partial y}\) in red.

If we differentiate again then \(\dfrac{\partial^{2} \sigma_{2}}{\partial^{2} x}(p)=\dfrac{\partial^{2} \sigma_{2}}{\partial x\partial y}(p)=0\) and \[\dfrac{\partial^{2} \sigma_{2}}{\partial^{2} y}(p)=\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ -\cos(y) \\ -\sin(y)\end{pmatrix}\] which belongs to \(T_{p}\Sigma_{2}^{\perp}\).

Even if \(\dfrac{\partial^{2} \sigma_{2}}{\partial^{2} y}\) is not constant unlike \(\dfrac{\partial^{2} \sigma_{2}}{\partial^{2} x}\), its derivative lie in \(T_{p}\Sigma^{\perp}\) and these vector fields are both parallel.

Obviously, a flat surface admits two parallel vector fields that spans its tangent space at every point : one can just choose constant vector fields tangent to the surfaces. Not every surface admits a non-zero parallel vector field as we will see. Nevertheless, we can always ask for a vector field to be parallel along a curve. Remember the geodesics : we saw that a curve \(\gamma\) was (locally) length minimizing if \(\gamma''(t)\in T_{p}\Sigma^{\perp}\) which is equivalent to say that the vector field \(t\to\gamma'(t)\) defined along \(\gamma\) is parallel along \(\gamma\).

We can adapt the geodesic equation, a second-order ODE on curves in \(\Sigma\), to vector fields along a fixed curve \(\gamma\) turning it into a first-order ODE :

Definition/Proposition 8. Let \(\Sigma\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) be a surface and \(\gamma:I\to\Sigma\) a smooth curve. A vector field along \(X:I\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) along \(\gamma\) that is tangent to \(\Sigma\) (\(X(t)\in T_{\gamma(t)}\Sigma\) for all \(t\in I\)) is said to be parallel along \(\Sigma\) if \(X'(t)\in T_{\gamma(t)}\Sigma^{\perp}\) for all \(t\in I\).

For all \(t_{0}\in I\) and \(X_{0}\in T_{\gamma(t_{0})}\Sigma\), there is a unique parallel vector field along \(\gamma\) such that \(X(t_{0})=X_{0}\).

If a parallel vector field along \(\gamma\) vanishes at one point it must vanish along \(\gamma\).

If a vector field \(\widetilde{X}\) is parallel along \(\Sigma\) then the vector field \(t\to \widetilde{X}_{\gamma(t)}\) is parallel along \(\gamma\).

Proof. Let \(N\) be a normal vector field along \(\Sigma\), the condition \(X'(t)\in T_{\gamma(t)}\Sigma^{\perp}\) is equivalent to \(X'(t)-\langle X'(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle N_{\gamma(t)}=0\iff X'(t)=\langle X'(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle N_{\gamma(t)}\). Since \(\langle X(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle=0\) we have \(\langle X'(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle+\langle X(t),N_{\gamma(t)}'\rangle=0\) and \(X\) will be parallel along \(\gamma\) iff \[X'(t)=-\langle X(t),N_{\gamma(t)}'\rangle N_{\gamma(t)}\]

Unlike the geodesic equation, we can properly solve the parallel transport equation with some ODE’s theory :

Define \(F:\mathbb{R}^{3}\times I\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) by \(F(X,t)=\langle X,N_{\gamma(t)}'\rangle N_\gamma(t)\)

Solve the differential equation : \(\begin{array}{ll} X(t_{0})=X_{0}\\ X'(t)=F(X(t),t) \end{array}\) This is a linear ODE and the solution will be defined on the whole interval \(I\).

Differentiating \(t\to\langle X(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle\) to \[\langle X'(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle+\langle X(t),N_{\gamma(t)}'\rangle=\langle -\langle X(t),N_{\gamma(t)}'\rangle N_{\gamma(t)},N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle+\langle X(t),N_{\gamma(t)}'\rangle=0\] yields \(\langle X(t),N_{\gamma(t)}\rangle=\langle X(t_{0}),N_{\gamma(t_{0})}\rangle=0\) since \(X_{0}\in T_{\gamma(t_{0})}\Sigma^{\perp}\).

Conclude that \(X(t)\) is orthogonal to \(N_{\gamma(t)}\) everywhere and therefore tangent to \(\Sigma\).

This proves (i).

(ii) is a standard result from the theory of linear ODE.

For (iii), setting \(p=\gamma(0)\) and \(v=\gamma'(0)\), observe that \(X'(t)=\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}\widetilde{X}_{\gamma(t)}=\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial v}=0\) and \(X\) is parallel along \(\gamma\).

◻

This gives us a way to move \(X_{0}\in T_{\gamma(t_{0})}\) along the curve \(\gamma\) to \(X(t)\in T_{\gamma(t)}\) : this is called parallel transport and it yields is a linear isometry between \(T_{\gamma(t_{0})}\Sigma\) and \(T_{\gamma(t)}\Sigma\)

Definition/Proposition 9. Let \(\Sigma\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) be a surface, \(\gamma:I\to\Sigma\) a smooth curve and \((t_{0},t_{1})\in I^{2}\) with \(t_{0}\leq t_{1}\)

We define \(\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}:T_{\gamma(t_{0})}\Sigma\to T_{\gamma(t_{1})}\Sigma\) by \(\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}(X_{0})=X(t_{1})\) where \(X\) is the parallel vector field along \(\gamma\) satisfying \(X(t_{0})=X_{0}\).

\(\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}\) is a linear.

\(\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}\) is an isometry and hence invertible.

Let \((t_{0},t_{1},t_{2})\in I^{3}\) with \(t_{0}\leq t_{1}\leq t_{2}\) then \(\Gamma_{t_{1}}^{t_{2}}\circ\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}=\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{2}}\)

The parallel transport for a continuous curve that is piecewise smooth is defined as the composition of the parallel transport along the curve restricted to the intervals upon which it is smooth which satisfies also properties (i)-(iii).

Proof. Let \(\gamma : I\to\Sigma\) be a smooth curve and \(X\), \(Y\) be parallel vector fields along \(\Sigma\) with \(X(t_{0})=X_{0}\) and \(Y(t_{0})=Y_{0}\).

Let \(\lambda\in\mathbb{R}\) be a scalar, then \(X+\lambda Y\) is also parallel takes the value \(X_{0}+\lambda Y_{0}\) at \(t=t_{0}\) to that \(\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}(X_{0}+\lambda Y_{0})=(X+\lambda Y)(t_{1})=X(t_{1})+\lambda Y(t_{1})=\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}(X_{0})+\lambda \Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}(Y_{0})\) and \(\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}\) is linear.

Let’s differentiate \(t\to\langle X(t),Y(t)\rangle\) to \(\langle X'(t),Y(t)\rangle+\langle X(t),Y'(t)\rangle=0\) since \(X'(t)\) and \(Y'(t)\) are orthogonal to \(X(t)\) and \(Y(t)\) that are tangent to \(\Sigma\).

This means \(\langle X(t_{0}),Y(t_{0})\rangle=\langle X(t_{1}),Y(t_{1})\rangle \iff \langle \Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}(X_{0}),\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}(Y_{0})=\langle X_{0},Y_{0}\rangle\).Let \(X\) be the parallel vector field with initial condition \(X(t_{0})=X_{0}\) and \(\widetilde{X}\) the parallel vector field with initial condition \(\widetilde{X}(t_{1})=X(t_{1})\). Both vector fields satisfy the parallel equation and they coincide at \(t=t_{1}\). They must be equal on the whole interval, or \(\widetilde{X}(t_{2})=\Gamma_{t_{1}}^{t_{2}}(X(t_{1}))=\Gamma_{t_{1}}^{t_{2}}(\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}(X_{0}))\) and \(X(t_{2})=\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{2}}(X_{0})\) so that \(\Gamma_{t_{1}}^{t_{2}}\circ\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}=\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{2}}\).

For a piecewise smooth curve the properties (i) and (ii) are immediate since the composition of linear isometries is a linear isometry and property (iii) is also immediate because the parallel transport for a piecewise smooth curves is obtained by composition. ◻

We don’t have yet the tools to prove it but parallel transport is actually an isometric invariant meaning that, given an isometry \(\phi:\Sigma_{1}\to\Sigma_{2}\) between two surfaces and a curve \(\gamma:I\to\Sigma_{1}\) then \(d\phi\) maps parallel vector fields along \(\gamma\) to parallel vector fields along \(\phi\circ\gamma\). It is equivalent to say that \(\phi\) commutes with parallel transport : let \(\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}\) (resp. \(\widetilde{\Gamma}_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}\)) denote the parallel transport along \(\gamma\) in \(\Sigma_{1}\) (resp. along \(\phi\circ\gamma\)) then \(d\phi_{\gamma(t_{1})}\circ\Gamma_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}=\widetilde{\Gamma}_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}\circ d\phi_{\gamma(t_{0})}\).

For a flat a surface \(S\) like a open subset of a 2 dimensional subspace \(V\) of \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\) , all the tangent spaces are canonically isomorphic to \(V\) via the map \(v\in V\to\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}(p+tv)\in T_{p}S\) and a parallel vector field (along a surface or a curve) is just a constant vector field. Modulo this identifications, the parallel transport along any curve is the identity. Now for a general surface \(\Sigma\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) that is not flat there is no natural isomorphism between its different tangent spaces as they vary in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\). Nevertheless, if we suppose that \(\Sigma\) is isometric to a flat surface then the parallel transport along any curve \(\gamma : I\to\Sigma\) maps \(T_{\gamma(0)}\Sigma\) to \(T_{\gamma_{1}}\Sigma\) and this isomorphism depends does not depend \(\gamma\).

More precisely, let \(\phi:\Sigma\to S\) be an isometry between \(\Sigma\) and \(S\) an open subset of 2 dimensional subspace , \(\gamma:I\to\Sigma\) a smooth curve and let \(\Gamma\) the parallel transport along \(\gamma\). Since \(\phi\) commutes with parallel transport and the parallel transport on \(S\) is the identity, we have \(d\phi_{\gamma(1)}\circ\Gamma_{0}^{1}=d\phi_{\gamma(0)}\) or \(\Gamma_{0}^{1}(X)=d\phi_{\gamma(1)}^{-1}\circ d\phi_{\gamma(0)}\). This result still holds for piecewise smooth curves.

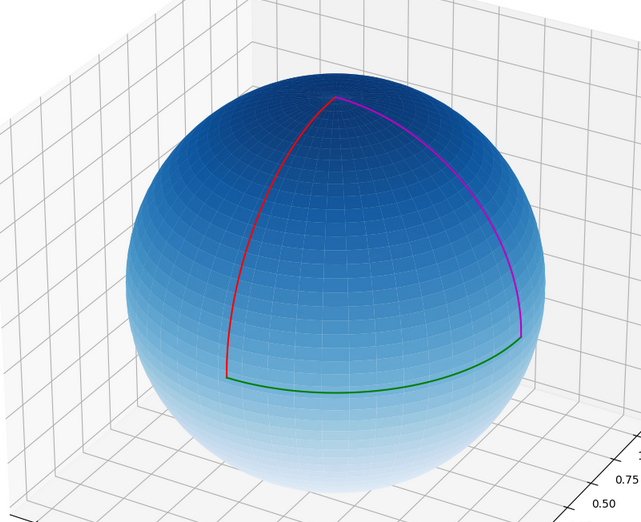

We are ready to exhibit a real curved surface in the sense that it can not be isometric to a flat open subset of \(\mathbb{R}^{2}\) : the (almost) sphere. We defined surfaces as images of smooth injective maps from an open subset of \(\mathbb{R}^{2}\) whose derivative has everywhere rank \(2\). The whole sphere can not be obtained this way but the sphere minus the south pole can via stereographic projection namely \(\sigma : \mathbb{R}^{2}\to\mathbb{R}^{3}\) defined by \(\sigma(x,y)=(\dfrac{2x}{1+x^{2}+y^{2}},\dfrac{2y}{1+x^{2}+y^{2}},\dfrac{1-x^{2}-y^{2}}{1+x^{2}+y^{2}})\) and this is enough for what we want to exhibit. We note \(\Sigma:=\sigma(\mathbb{R}^{2})\) be the sphere minus the south pole.

Let

\(\gamma_{1}:[-\dfrac{\pi}{2},0]\to\Sigma\) be defined by \(\gamma_{1}(t)=(0,\sin(t),\cos(t))\)

\(\gamma_{2}:[0,\dfrac{\pi}{2}]\to\Sigma\) be defined by \(\gamma_{2}(t)=(\cos(t),0,\sin(t))\)

\(\gamma_{3}:[-\dfrac{\pi}{2},0]\to\Sigma\) be defined by \(\gamma_{3}(t)=(\cos(t),\sin(t),0)\)

\(\gamma_{1}\) in red, \(\gamma_{2}\) in purple and \(\gamma_{3}\) in green.

Let \(p=(0,-1,0)\) and \(X_{1}=(0,0,1)\in T_{p}\Sigma\). The parallel transport along \(\gamma_{1}\) send \(X_{1}\) to \(X_{2}=(1,0,0)\) and the parallel transport along \(\gamma_{2}\) sends \(X_{2}\) to \(X_{2}\) but the parallel transport along \(\gamma_{3}\) sends \(X_{1}\) to \(X_{1}\) which means that that \(\gamma_{3}\) and \(\widetilde{\gamma}\), the concatenation of \(\gamma_{1}\) and \(\gamma_{2}\) that is piecewise smooth have the same extremities but move vectors differently. Hence, the sphere can not be isometric to a flat surface.

The existence parallel vector fields that on \(\Sigma\) and the independence of parallel transport towards the path from one point to another are both equivalent to a third phenomenon : the commutativity of covariant derivatives.

Definition/Proposition 10. Let \(\Sigma:=\sigma(U)\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) be a parametrized surface with \(U=I\times J\) a rectangle and \(N\) a normal vector field for \(\Sigma\). We denote \(\mathcal{X}(\Sigma)\) the space of tangent vector fields along \(\Sigma\).

Let \(p=\sigma(x,y)\in\Sigma\) and denote \(\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial x}(p):=\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}X_{\sigma(x+t,y)}\). We define the covariant derivative in the \(x\)-direction \(D_{x}:\mathcal{X}(M)\to\mathcal{X}(M)\) by \(D_{x}(X)(p):=\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial x}(p)-\langle\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial x}(p),N_{p}\rangle N_{p}\in T_{p}\Sigma\) which maps smooth tangent vector fields to smooth tangent vector fields.

Similarly we define the covariant derivative in the \(y\)-direction \(D_{y}:\mathcal{X}(M)\to\mathcal{X}(M)\) .

For any smooth function \(f:\Sigma\to\mathbb{R}\) and any vector field \(X\in\mathcal{X}(M)\) we have \(D_{x}(fX)=\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x}X+fD_{x}(X)\) where \(\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x}(p)=\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}f\circ\sigma(x+t,y)\).

Similarly : \(D_{y}(fX)=\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}X+fD_{y}(X)\)A vector field \(X\) satisfies \(D_{x}(X)=0\) (resp. \(D_{y}(X)=0\)) iff the restriction of \(X\) to any smooth curve \(\gamma : I\to \Sigma\) of the form \(\gamma(t)=\sigma(x+t,y)\) (resp. \(\gamma(t)=\sigma(x,y+t)\) ) is parallel along \(\gamma\).

Just like parallel transport and parallel vector fields, covariant derivatives are an isometric invariant in a sense that we will precise later.

Definition/Proposition 11. Let \(\Sigma\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) be a parametrized surface, \(N\) a normal vector field for \(\Sigma\), \(D_{x}\) and \(D_{y}\) the covariant derivatives in the \(x\) and \(y\) directions.

The following conditions are equivalent :

There exists parallel vector fields \(\widetilde{X}\) and \(\widetilde{Y}\) such that \(\{X_{p},Y_{p}\}\) is a orthonormal basis of \(T_{p}\Sigma\).

The parallel transport along every smooth curve \(\gamma : [0,1]\to\Sigma\) depends only on the end points \(\sigma(0)\) and \(\sigma(1)\).

\(D_{x}\circ D_{y}=D_{y}\circ D_{x}\).

Proof.

Let \(\gamma : [0,1]\to\Sigma\) be a smooth curve and \(p:=\gamma(0)\), \(q:=\sigma(1)\). Let \(X\in T_{p}\Sigma\), there exists \((\lambda,\mu)\in\mathbb{R}^{2}\) such that \(X=\lambda\widetilde{X}_{p}+\mu\widetilde{Y}_{p}\). The vector field \(\widetilde{Z}:=\lambda\widetilde{X}+\mu\widetilde{Y}\) is parallel along \(\Sigma\) and its restriction to \(\gamma\), that is \(t\to Z_{\gamma(t)}\), is parallel along \(\gamma\). This means that the parallel transport of \(X\) along \(\gamma\) must be equal to \(\widetilde{Z}_{q}=\lambda\widetilde{X}_{q}+\mu\widetilde{Y}_{q}\) and depends only on \(p\) and \(q\).

Let \(p\in \Sigma\) and \((X_{p},Y_{p})\in T_{p}\Sigma^{2}\) be a orthonormal basis of the tangent space at \(p\). We define \(\widetilde{X}\in\mathcal{X}(M)\) (resp. \(\widetilde{Y}\in\mathcal{X}(M)\)) to be the tangent vector field on \(\Sigma\) whose value at \(q\) is the parallel transport of \(X_{p}\) (resp. \(Y_{p}\)) along any smooth map \(\sigma:[0,1]\to\Sigma\) satisfying \(\sigma(0)=p\) and \(\sigma(q)=1\).

Since the parallel transport along a curve is an isometry, \(\{\widetilde{X}_{q},\widetilde{Y}_{q}\}\) is an orthonormal basis of \(T_{q}\Sigma\) at every point \(q\in \Sigma\) and it’s easy to show that \(\widetilde{X}\) and \(\widetilde{Y}\) are parallel vector fields.

Let \(Z\in\mathcal{X}(M)\). Since \(\{\widetilde{X}_{q},\widetilde{Y}_{q}\}\) is an orthonormal basis of \(T_{p}\Sigma\) at every point \(p\in\Sigma\) we have \(Z=\langle Z,\widetilde{X}\rangle\widetilde{X}+\langle Z,\widetilde{Y}\rangle\widetilde{Y}\). Let \(f:\Sigma\to\mathbb{R}\) (resp. \(g:\Sigma\to\mathbb{R}\)) be defined by \(f(p)=\langle Z_{p},\widetilde{X}_{p}\rangle\) (resp. \(g(p)=\langle Z_{p},\widetilde{Y}_{p}\rangle\)).

Both \(f\) and \(g\) are smooth maps and : \[D_{y}(Z)=D_{y}(f\widetilde{X})+D_{y}(g\widetilde{Y})=\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}\widetilde{X}+fD_{y}\widetilde{X}+\dfrac{\partial g}{\partial y}\widetilde{Y}+gD_{y}\widetilde{Y}=\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}\widetilde{X}+\dfrac{\partial g}{\partial y}\widetilde{Y}\] since \(\widetilde{X}\) and \(\widetilde{Y}\) are parallel. Feeding this expression to \(D_{x}\) yields \[D_{x}\circ D_{y}(Z)=\dfrac{\partial^{2} f}{\partial x\partial y}\widetilde{X}+\dfrac{\partial^{2} g}{\partial x\partial y}\widetilde{Y}\] which is symmetric in \(x\) and \(y\) so that \(D_{x}\circ D_{y}(Z)=D_{y}\circ D_{x}(Z)\).

Let \((x,y)\in I\times J\), \(p=\sigma(x,y)\) and \(\{X_{p},Y_{p}\}\) be any orthonormal basis of \(T_{p}\Sigma\). We first extend \(X_{0}\) (resp. \(Y_{0}\)) along \(\gamma_{1}:I\to\Sigma\) defined by \(\gamma(t)=\sigma(0,t)\) to a parallel vector field and then extend it along each \(\gamma_{t}:J\to\Sigma\) defined by \(\gamma_{t}(s)=\sigma(s,t)\) to get a tangent vector field \(\widetilde{X}\) (resp. \(\widetilde{Y}\)) on \(\Sigma\). Since parallel transport is isometric, \(\{\widetilde{X}_{q},\widetilde{Y}_{q}\}\) is an orthonormal basis of \(T_{q}\Sigma\) at every point \(q\in\Sigma\).

By construction we have \(D_{x}(\widetilde{X})_{p}=0\) for all \(p\in\Sigma\) and \(D_{y}(\widetilde{X})_{\sigma(0,t)}=0\) for all \(t\in J\). Now define \(Z=D_{y}\widetilde{X}\), then \(D_{x}(Z)=D_{x}\circ D_{y}(\widetilde{X})=D_{y}\circ D_{x}(\widetilde{X})=0\) so \(Z\) in parallel along each \(\gamma_{t}\) and at \(p=\gamma(s,t)\) : \(Z_{\gamma_{t}(0)}=D_{x}(\widetilde{X})_{\sigma(0,t)}=0\). The vector field \(Z\) vanishes along all \(\gamma_{t}\) hence on all \(\Sigma\) and \(\widetilde{X}\) is parallel. The same holds for \(\widetilde{Y}\).

We have two vector fields \(\widetilde{X}\) and \(\widetilde{Y}\) that satisfies \(D_{x}(X)=D_{y}(X)=0\) that is \(\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial x}=\langle\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial x},N\rangle N\) and \(\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial y}=\langle\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial y},N\rangle N\) and similarly for \(Y\).

Let \(p\in\Sigma\) and \(v\in T_{p}\Sigma\). There exists \((\lambda,\mu)\in\mathbb{R}^{2}\) such that \(v=\lambda\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial x}+\mu\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial y}\) which implies \(\dfrac{\partial \widetilde{X}}{\partial v}=\lambda\dfrac{\partial \widetilde{X}}{\partial x}+\mu\dfrac{\partial \widetilde{X}}{\partial y}=\lambda\langle\dfrac{\partial \widetilde{X}}{\partial x},N\rangle N+\mu\langle\dfrac{\partial \widetilde{X}}{\partial y},N\rangle N\in T_{p}\Sigma^{\perp}\) so that \(\widetilde{X}\) is parallel along \(\Sigma\). The same holds for \(\widetilde{Y}\).

◻

Remarks 1.

Mimicking the proof of (iii)\(\implies\)(i), we can still show that there exists tangent vector fields on \(\Sigma\) that are parallel in one direction. The default of commutativity between \(D_{x}\) and \(D_{y}\) measure the obstruction for such a vector to be parallel in the other direction.

This result was proved for a rectangle that is easy to work with. The readers that are familiar with homotopy of paths and the fundamental group that this still holds for an open simply connected set \(U\subset\mathbb{R}^{2}\) but may fail otherwise.

Even if the covariant derivatives commute, the parallel transport along non homotopic paths may differ or, equivalently, parallel transport along a non null-homotopic loop based at \(p\in \Sigma\) may yield a non trivial isometry of \(T_{p}\Sigma\). Nevertheless, it can be shown using the same techniques that two homotopic loops based at \(p\) will give the same isometry and we get a group representation \(\pi_{1}(\Sigma,p)\to O(T_{p}\Sigma)\) : this is called monodrony.

Let’s now compute \(D_{x}\circ D_{y}-D_{y}\circ D_{x}\) : let \(Z\in\mathcal{X}(M)\) be a tangent vector field. We have \[D_{y}(Z)=\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial y}-\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial y},N\rangle N\]

\[D_{x}(D_{y}(Z))=\dfrac{\partial^{2}Z}{\partial x\partial y}-\langle\dfrac{\partial^{2}Z}{\partial x\partial y},N\rangle N-\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial y},\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}\rangle N-\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial y},N\rangle \dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}\]

Similarly we get \[D_{y}\circ D_{x}(Z)=\dfrac{\partial^{2}Z}{\partial x\partial y}-\langle\dfrac{\partial^{2}Z}{\partial x\partial y},N\rangle N-\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial x},\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y}\rangle N-\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial x},N\rangle \dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y}\] and

\[(D_{x}\circ D_{y}-D_{y}\circ D_{x})(Z)=(\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial x},\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y}\rangle-\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial y},\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}\rangle)N+\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial x},N\rangle \dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y}-\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial y},N\rangle \dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}\]

We know that \(D_{x}\circ D_{y}-D_{y}\circ D_{x}\) takes \(\mathcal{X}(\Sigma)\) to \(\mathcal{X}(\Sigma)\) and so the right hand side is orthogonal to \(N\). Also \(\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}\) and \(\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y}\) are tangent to \(\Sigma\) so that \(0=\langle(D_{x}\circ D_{y}-D_{y}\circ D_{x})(Z),N\rangle=\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial x},\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y}\rangle-\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial y},\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}\rangle\) and

\[(D_{x}\circ D_{y}-D_{y}\circ D_{x})(Z)=\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial x},N\rangle \dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y}-\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial y},N\rangle \dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}\]

Finally, an integration by parts yield the nicer formula \[(D_{x}\circ D_{y}-D_{y}\circ D_{x})(Z)=\langle Z,\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y}\rangle\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}-\langle Z,\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}\rangle\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y}\]

Why "nicer"? Because, written this way, we can see that the value of \[(D_{x}\circ D_{y}-D_{y}\circ D_{x})(Z)\] at \(p\in\Sigma\) only depends on the value of \(Z_{p}\) contrarly to \(D_{x}\) and \(D_{y}\) and this dependence is linear. In otherwords, \(D_{x}\circ D_{y}-D_{y}\circ D_{x}\) determines and is uniquely determined by a collection of endomorphism \(R_{p}\) of \(T_{p}\Sigma\) for \(p\in\Sigma\) defined by \(R_{p}(v)=\langle v,\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y}\rangle\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}-\langle v,\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}\rangle\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y}\).

It turns out that this endormophism is antisymmetric with respect to the ambient euclidean scalar product : let \((z,w)\in T_{p}\Sigma^{2}\) then

\[\langle R_{p}(z),w\rangle=\langle z,\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y}\rangle\langle\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x},w\rangle-\langle z,\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}\rangle\langle\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial y},w\rangle\]

This kinda looks familiar, remember the second fundamental form \(\mathbb{I}_{p}\)? Remember that \(\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}(p)\) (resp. \(\dfrac{\partial N}{\partial x}(p)\) ) is the derivative of the normal vector field \(N\) at \(p\) with respect to the tangent vector \(\dfrac{\partial\sigma}{\partial x}\) (resp. \(\dfrac{\partial\sigma}{\partial y}\)) so that

\[\langle R_{p}(z),w\rangle=\mathbb{I}_{p}(z,\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial y})\mathbb{I}_{p}(w,\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial x})-\mathbb{I}_{p}(z,\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial x})\mathbb{I}_{p}(w,\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial y})\]

We’d like to say that \(R_{p}\) is an isometric invariant. The problem is that it is defined with some parameterization of \(\Sigma\). The goal of the next sections is to introduce some parameterization-free version of \(R_{p}\) : the Levi-Civita connection and the Riemann curvature operator that are actual isometric invariants.

The Levi-Civita connection for surfaces

To show how vector fields differentiation is an isometric invariant, we need to precise how an isometry acts on vector fields.

Definition/Proposition 12. Let \(\phi:\Sigma_{1}\to\Sigma_{2}\) be a diffeomorphism.

For a vector field \(X\in \mathcal{X}(\Sigma_{1})\) let \(\phi_{\star}(X)\in\mathcal{X}(\Sigma)\) be defined by \(\phi_{\star}(X)\in\mathcal{X}(\Sigma_{2})\) by \(\phi_{\star}(X)_{q}=d\phi_{\phi^{-1}(q)}(X_{\phi^{-1}}(q))\) for \(q\in\Sigma_{2}\). This is equivalent to \(\phi_{\star}(X)_{\phi(p)}=d\phi_{p}(X_{p})\). It is a smooth vector field tangent to \(\Sigma_{2}\) called the pushforward of \(X\) by \(\phi\).

The map \(\phi_{\star}:\mathcal{X}(\Sigma_{1})\to\mathcal{X}(\Sigma_{2})\) is a linear isomorphism. Even better : we can multiply smooth vector fields by smooth functions so that \(\mathcal{X}(\Sigma_{1})\) (resp. \(\mathcal{X}(\Sigma_{Z})\)) has a \(C^{\infty}(\Sigma_{1},\mathbb{R})\)-module (resp. \(C^{\infty}(\Sigma_{1},\mathbb{R})\)-module). This structure is also preserved by \(\phi_{\star}\) in the sense that : \(\phi_{\star}(fX)=f\circ\phi^{-1}\phi_{\star}(X)\) for \(f\in C^{\infty}(\Sigma_{1},\mathbb{R})\).

For any pair of diffeomorphism \(\phi\) and \(\psi\) :

\((\phi\circ\psi)_{\star}=\phi_{\star}\circ\psi_{\star}\)

\((\mathop{\mathrm{Id}}_{\Sigma_{1}})_{\star}=\mathop{\mathrm{Id}}_{\mathcal{X}(\Sigma_{1})}\)

\(\phi^{-1}_{\star}=(\phi_{\star})^{-1}\)

Proof. For \(f\in C^{\infty}(\Sigma_{1},\mathbb{R})\) we have :\(\phi_{\star}(fX)_{\phi(p)}=d\phi_{p}(f(p)X_{p})=f(p)d\phi_{p}(X_{p})\) so that \(\phi_{\star}(fX)=(f\circ\phi^{-1})\phi_{\star}(X)\).

◻

Let \(\Sigma\subset \mathbb{R}^{3}\) be a surface and \(N\) a normal vector field for \(\Sigma\). The ambient scalar product of \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\) induces an euclidean structure on every tangent space \(T_{p}\Sigma\) for \(p\in\Sigma\). Except for flat surfaces, \(\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial v}(p)\) needs not to be a tangent vector field but we circumvented this problem by projecting it orthogonally on \(T_{p}\Sigma\) thanks to the normal vector \(N\).

If the dynamics of \(N\) along \(\Sigma\) depends on the way \(\Sigma\) lies in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\) and not only on the metric structure of \(\Sigma\) it turns out that this tool to differentiate tangent vector fields to tangent vector fields is an isometric invariant.

Definition/Proposition 13. Let \(\Sigma\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) be a surface.

We define the Levi-Civita connection to be the bilinear map \(\mathcal{X}(\Sigma)\times \mathcal{X}(\Sigma)\to\mathcal{X}(\Sigma)\) by \((X,Y)\to\nabla_{X}Y\) with \(\nabla_{X}Y(p)=\dfrac{\partial Y}{\partial X_{p}}(p)-\langle\dfrac{\partial Y}{\partial X_{p}}(p),N_{p}\rangle N_{p}\). It is the covriant derivative of \(Y\) with respect to \(X\) and it satisfies :

\(\nabla_{fX}Y=f\nabla_{X}Y\) for any \(f\in C^{\infty}(\Sigma,\mathbb{R})\)

\(\nabla_{X}(fY)=\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial X}Y+f\nabla_{X}Y\) for any \(f\in C^{\infty}(\Sigma,\mathbb{R})\)

\(\nabla_{X}Y-\nabla_{Y}X=[X,Y]\) the Lie bracket introduced in Definition/Proposition 6.

\(\dfrac{\partial \langle Y,Z\rangle}{\partial X}=\langle\nabla_{X},Y,Z\rangle+\langle Y,\nabla_{X}Z\rangle\)

After introducing the basis of differential and abstract Riemannian geometry, we will prove in the next section that this map is uniquely determined by the metric structure.

Theorem 1. Let \(\Sigma\subset\mathbb{R}^{3}\) be a surface.

Any linear map \(\mathcal{X}(\Sigma)\times \mathcal{X}(\Sigma)\to\mathcal{X}(\Sigma)\) satisfying conditions (i)-(iv) of definition/proposition Definition/Proposition 13 must be equal to the Levi-Civita connection.

Corollary 1. Let \(\phi : \Sigma_{1}\to\Sigma_{2}\) be an isometry between surfaces and let \(\nabla^{1}\) (resp. \(\nabla^{2}\)) be the Levi-Civita connection of \(\Sigma_{1}\) (resp. \(\Sigma_{2}\)).

For any pair of vector fields \((X,Y)\in \mathcal{X}(\Sigma_{1})^{2}\), we have :

\[\phi_{\star}(\nabla^{1}_{X}(Y))=\nabla^{2}_{\phi_{\star}(X)}\phi_{\star}Y\]

Proof. For \((X,Y)\in \mathcal{X}(\Sigma_{1})^{2}\) define \(\widetilde{\nabla}_{X}Y\) by \[\widetilde{\nabla}_{X}Y=\phi_{\star}^{-1}(\nabla^{2}_{\phi_{\star}(X)}\phi_{\star}Y)\]

We shall prove that \(\widetilde{\nabla}\) satisfies the defining properties of the Levi-Civita connection.

Properties (i)-(iii)no dot depend on the isometric property of \(\phi\) and are valid for any diffeomorphism. We will still show (i)-(iii) to prepare ourselves for the differential geometric machinery that awaits us later. Even if it may look like a computational nightmare, it’s mainly a successive applications of definitions.

\[\widetilde{\nabla}_{fX}Y=\phi_{\star}^{-1}(\nabla^{2}_{\phi_{\star}(fX)}\phi_{\star}Y))=\phi_{\star}^{-1}(\nabla^{2}_{(f\circ\phi^{-1})\phi_{\star}(X)}\phi_{\star}Y)\] \[=\phi_{\star}^{-1}((f\circ\phi^{-1})\nabla^{2}_{\phi_{\star}(X)}\phi_{\star}Y) =(f\circ\phi^{-1}\circ\phi)\phi_{\star}^{-1}(\nabla^{2}_{\phi_{\star}(X)}\phi_{\star}Y)=f\widetilde{\nabla}_{X}Y\]

\[\widetilde{\nabla}_{X}(fY)=\phi_{\star}^{-1}(\nabla^{2}_{\phi_{\star}(X)}\phi_{\star}(fY))=\phi_{\star}^{-1}(\nabla^{2}_{\phi_{\star}(X)}(f\circ\phi^{-1})\phi_{\star}Y)\] \[=\phi_{\star}^{-1}(\dfrac{\partial (f\circ\phi^{-1})}{\partial \phi_{\star}X}\phi_{\star}(Y)+ (f\circ\phi^{-1})\nabla^{2}_{\phi_{\star}(X)}\phi_{\star}Y)\] \[=(\dfrac{\partial (f\circ\phi^{-1})}{\partial \phi_{\star}X}\circ\phi)Y+f\widetilde{\nabla}_{X}(Y)\]

The term \(\dfrac{\partial (f\circ\phi^{-1})}{\partial \phi_{\star}X}\circ\phi\) looks hardcore but indeed : take a curve \(\gamma:I\to\Sigma_{1}\) satisfying \(\gamma(0)=p\) and \(\gamma'(0)=X_{p}\) then \(\widetilde{\gamma}=\phi\circ\gamma\) satisfies \(\widetilde{\gamma}(0)=\phi(p)\) and \(\widetilde{\gamma}'(0)=d\phi_{p}(v)=\phi_{\star}(X)_{\phi(p)}\). We can compute \(\dfrac{\partial (f\circ\phi^{-1})}{\partial \phi_{\star}X}(\phi(p))\) as \(\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}f\circ\phi^{-1}\circ\widetilde{\gamma}(t)=\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}f\circ\gamma(t)=\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial v}(p)=\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial X}(p)\) so that \(\dfrac{\partial (f\circ\phi^{-1})}{\partial \phi_{\star}X}\circ\phi=\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial X}\) which proves (ii)

We will prove later that \(\phi_{\star}([X,Y])=[\phi_{\star}(X),\phi_{\star}(Y)]\) when investigating the Lie Bracket on a manifold. Granted this equality, the proof is left as an exercise.

This is where the isometric character intervenes : for all vector fields \((Y,Z)\in\mathcal{X}(\Sigma_{1})^{2}\) : \(\langle\phi_{\star}Y,\phi_{\star}Z\rangle\circ\phi=\langle X,Z\rangle\).

\[\langle\widetilde{\nabla}_{X}Y,Z\rangle+\langle Y,\widetilde{\nabla}_{X}Z\rangle =\langle \phi_{\star}^{-1}(\nabla^{2}_{\phi_{\star}(X)}\phi_{\star}Y),Z\rangle +\langle Y, \phi_{\star}^{-1}(\nabla^{2}_{\phi_{\star}(X)}\phi_{\star}Z) \rangle\] \[=\langle \nabla^{2}_{\phi_{\star}(X)}\phi_{\star}Y,\phi_{\star}Z\rangle\circ\phi +\langle \phi_{\star}Y, \nabla^{2}_{\phi_{\star}(X)}\phi_{\star}Z \rangle\circ\phi\]\[=\dfrac{\partial \langle \phi_{\star}Y,\phi_{\star}Z\rangle}{\partial \phi_{\star}(X)}\circ\phi=\dfrac{\partial (\langle Y,Z\rangle\circ\phi^{-1})}{\partial\phi_{\star}(X)}\circ\phi=\dfrac{\partial \langle Y,Z\rangle}{\partial X}\]

◻

The Levi-Civita connection is indeed an isometric invariant : the vector space isomorphism \(\phi_{\star}:\mathcal{X}(\Sigma_{1})\to \mathcal{X}(\Sigma_{2})\) induced by an isometry is compatible with the Levi-Civita connections of both surfaces.

For a parametrized surface \(\Sigma:=\sigma(U)\) we saw earlier that \(D_{x}\circ D_{y}-D_{y}\circ D_{x}\) measured the obstruction to the existence of non zero parallel vector fields. The drawback was that this operator depends on the parameterization.

Remember from definition Definition/Proposition 10 that \(D_{x}(Z)=\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial x}(p)-\langle\dfrac{\partial Z}{\partial x}(p),N_{p}\rangle N_{p}\). We abbreviated \(\dfrac{\partial X}{\partial x}\) for \(\dfrac{d}{dt}_{t=0}X_{\sigma(x+t,y)}\) so that \(D_{x}(Z)\) is \(\nabla_{\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial x}}Z\).

Notice that, in terms of pushforward, \(\dfrac{\partial \sigma}{\partial x}=\phi_{\star}(\dfrac{\partial}{\partial x})\) where \(\dfrac{\partial}{\partial x}\) is the constant vector field on the domain of \(\sigma\) equal to \((1,0)\). The notation might look weird at first glance but it will make sense later.

To have a parametrization-free expression of \(D_{x}\circ D_{y}-D_{y}\circ D_{x}\) we might be tempted to define a map \(\mathcal{X}(\Sigma)^{3}\to\mathcal{X}(\Sigma)\) by \[(X,Y,Z)\to \nabla_{X}\nabla_{Y}Z-\nabla_{Y}\nabla_{X}Z\]

The problem is that, even for flat surfaces, this operator is non zero. This is not a metric phenomenon, rather a "differential" one. Let \(f:\mathbb{R}^{2}\to\mathbb{R}\). The Schwarz’s theorem on the symmetry of partial derivatives assert that \(\dfrac{\partial }{\partial x}(\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y})=\dfrac{\partial }{\partial y}(\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x})\) that is, the vector fields \(\dfrac{\partial }{\partial x}\) and \(\dfrac{\partial }{\partial y}\) seen as operators on \(C^{\infty}(\mathbb{R}^{2},\mathbb{R})\) commute.

Now take the vector fields \(X\) defined by \(X_{(x,y)}=y\dfrac{\partial }{\partial x}\) and \(Y=\dfrac{\partial }{\partial y}\). For any \(h\in C^{\infty}(\mathbb{R}^{2},\mathbb{R})\) :

\(\dfrac{\partial }{\partial X}(\dfrac{\partial}{\partial Y}h)=y\dfrac{\partial }{\partial x}(\dfrac{\partial }{\partial y}h)=y\dfrac{\partial^{2} h}{\partial x\partial y}\)